T

eamwork

If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

Here's the thing. You don't actually need a team to run a virtual camp. If you want to plan it all yourself and (wo)man each of the video calls, it's technically possible to be a one-person team. However, it will be much less stressful to have others by your side.

As you're building your team, these are a few considerations you might want to keep in mind:

- Play to people's strengths. Some people are more enthusiastic if you involve them from the start. If they help decide what the camp will entail, you'll have them hooked. Other people just want you to tell them what you need. They don't want to plan or don't have the time to do so, but are happy to be responsible for logging on and running a simple activity.

- See if you can involve some youth members. They might value a chance to share in the sisterhood and show off their leadership skills.

- There's no reason the girls in your unit can't be responsible for planning and running portions of the camp as they would with an in-person one too!

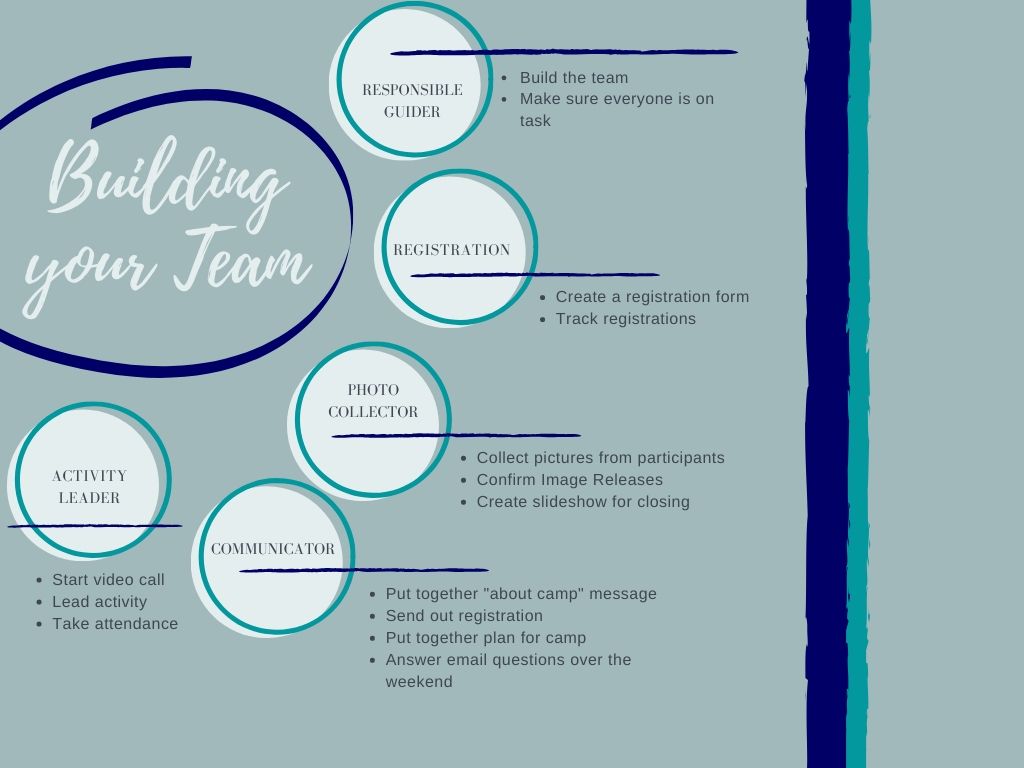

Here's an idea of some of the roles other volunteers can take on. You'll need to modify the tasks to suit your plans, but it's a good starting place.

What about if your team is feeling a little distant?

One of the wonderful things about the Guiding sisterhood if that Guiding sisters are never far away. There are wonderful Facebook communities chock full of fabulous ideas for any type of programming. Here are a few but I bet you can find more local ones too!

- "Do at home" Guiding program ideas

- GGC - Guide Leaders

- Girl Guide Program Ideas

- Guiders of Canada - unofficial

- GGC-Pathfinder/Ranger/Trex/Extra Ops Guiders

- GGC-GdC Québec

- Saskatchewan Girl Guides

- Ontario Girl Guides - unofficial

- Ontario Girl Guides - Leaders Only

- BC Girl Guides - Unofficial

- Guides du Canada - groupe non officiel pour cheftaine

I wrote my first assignment this semester about Facebook communities of practice so I would like to quote from it here as I am proposing that Guiders use that platform for connecting.

Communities of practice are defined as groups where there is a “process of collective learning in a shared domain of human endeavor” and require a domain (shared interest), a community (set of relationships) and practice (active involvement in knowledge sharing and/or creation) (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015, p. 1–2). The types of exchanges range from problem solving and requesting information to disseminating news and organizing in person interactions (Chiu et al., 2006; Evangelou & Karacapilidis, 2005; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015).

There are many elements to consider when choosing a platform, but the first argument for using Facebook is its accessibility. Not only do a large percentage of adults already have accounts, they are free to create and easy to jump in and out of as they do not require opening yet another account when the platform is already in use. Facebook users come from all geographies and time zones so it is simple to reach across borders to find information and share at any time of day or night, extending learning outside of regular zones. Choosing robust technology that simplifies use means that participation – and thus, learning – is more likely to occur on an ongoing basis (Chen, 2007; Evangelou & Karacapilidis, 2005; Kenney et al., 2013; Weller, 2007).

Another point in Facebook’s favour is its ability to foster connectivist learning. Connectivism sees learning as not occurring within a single person but within the connections we form between problems and those with specialized knowledge to solve them. It is an ongoing process where information is constantly shifting and coming into existence but is not under anyone’s individual control (Siemens, 2005, p. 5). Not only can a Facebook group connect those with differing opinions when users post questions in the open, the relationships built can quickly connect problems with those who have the knowledge required to solve them (Aaen & Dalsgaard, 2016; Cross et al., 2001), two elements crucial to connectivism (Siemens, 2005). What is routinely controlled by the educator can now be controlled by the learners themselves (Weller, 2007).

References

Aaen, J., & Dalsgaard, C. (2016). Student facebook groups as a third space: Between social life and schoolwork. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(1), 160–186.

Chen, I. Y. L. (2007). The factors influencing members’ continuance intentions in professional virtual communities - A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Information Science, 33(4), 451–467.

Chiu, C. M., Hsu, M. H., & Wang, E. T. G. (2006). Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decision Support Systems, 42(3), 1872–1888.

Cross, R., Parker, A., Prusak, L., & Borgatti, S. P. (2001). Knowing what we know: Supporting knowledge creation and sharing in social networks. Organizational Dynamics, 30(2), 100–120.

Evangelou, C., & Karacapilidis, N. (2005). On the interaction between humans and knowledge management systems: A framework of knowledge sharing catalysts. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 3(4), 253–261.

Kenney, J., Kumar, S., & Hart, M. (2013). More than a social network: Facebook as a catalyst for an online educational community of practice. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 1(4), 355.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism as a learning theory for the Digital Age. 1–9.

Weller, M. (2007). The distance from isolation. Why communities are the logical conclusion in e-learning. Computers & Education, 49(2), 148–159.

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/